Picasso Guernica Part.1

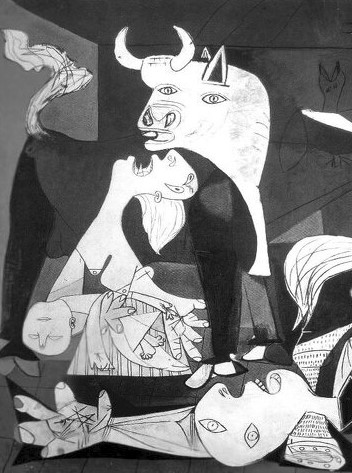

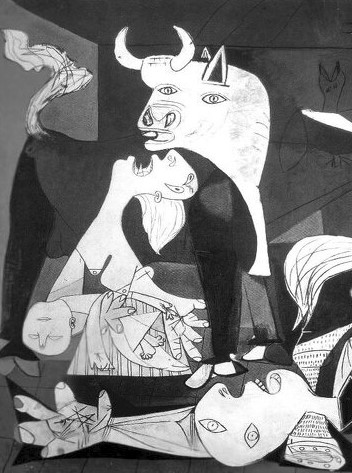

I. Picasso’s Guernica:

The Tragedy Unleashed

The tragedy unfolded on April 26, 1937, when a squadron of Nazi bombers launched a sudden and devastating attack on the town of Guernica in Spain. This calculated act of aggression was intended to provide support for General Franco. The news of this unwarranted assault echoed across the entire world. The following day, on the 27th, The Times published an an article that unveiled the immense scale and destructive impact of the onslaught, which had left an entire city in ruins.

Amidst the tumultuous Spanish Civil War, the city of Guernica, nestled far from the frontlines, had hitherto remained uninvolved and enjoyed a state of relative tranquility. Yet, devoid of any forewarning, this venerable city fell victim to indiscriminate bombings and ruthless machine gun fire. Thus, it was a corollary that the bombings elicited a torrent of condemnation from Picasso and around the world.

—

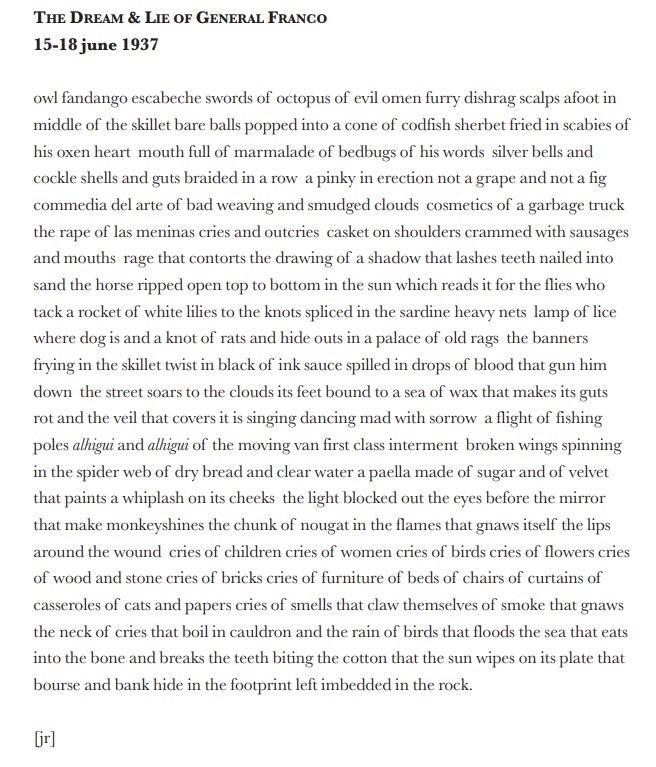

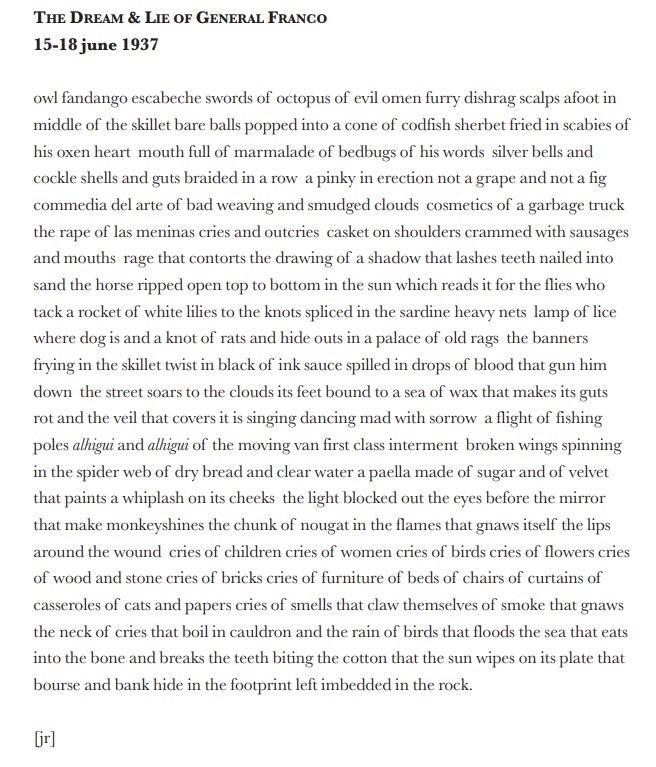

Picasso had unequivocally his staunch opposition to Franco even prior to the tragic events of Guernica and conveyed his allegiance to the Republican mainly through the sale of his artworks and donations. However, as the military clout of the Republicans began to wane in the early months of 1937, Picasso initiated his own form of attack against Franco. One notable result of this effort emerged in the form of a two-part print album christened “Dream and Lie of Franco.”

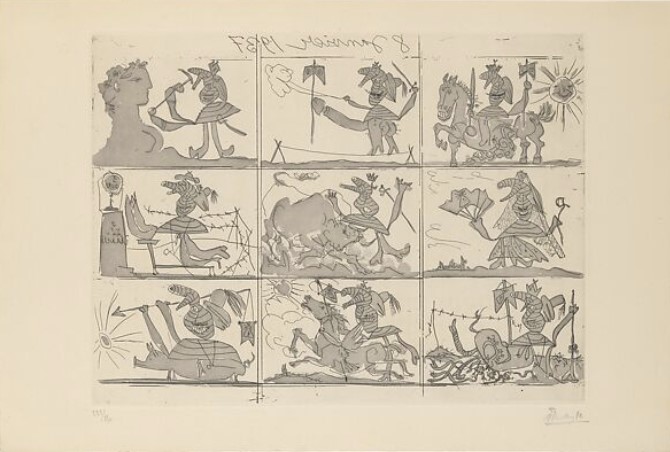

The composition is meticulously partitioned into nine discrete segments, each vividly portraying nightmarish creatures tormenting people. It becomes evident to any observer that the album targets the Francisco Franco regime. These poignant and evocative visuals evokes the somber world of “Guernica.” It is as if Picasso, with his sharp artistic intuition, foresaw the impending tragedy.

While the initial plan was to create 18 separate prints, a decision was made to consolidate these nine compelling images into a unified composition, as it was deemed to be more potent statement in a single form. The themes of the 18 artworks are as follows:

- Franco riding a horse waving a sword and a flag

- Franco, with a ridiculously large penis, waving a sword and a flag

- Franco attacking a classical sculpture with a pick

- Franco dressed as a courtesan with a flower and a fan

- Franco being gored by a bull

- Franco at prayer surrounded by barbed wire

- Franco on top of a dead creature[clarification needed]

- Franco chasing a winged horse

- Franco riding on a pig carrying a spear

- Franco eating a dead horse

- The aftermath of a battle with a corpse

- The aftermath of a battle with a dead horse

- Franco and a bull

- Franco and the bull fighting

- A woman crying and reaching up

- A woman fleeing a burning house carrying a child

- A woman cradling a child

- A woman shot with an arrow and reaching up amid devastation

Picasso also wrote a prose poem as a companion to the “Dream and Lie of Franco” print album. Upon reading the poem and closely scrutinizing the prints in “Dream and Lie of Franco”, one may discern numerous visuals that align with the themes articulated in the prose.

II. The Motifs in Guernica

Picasso, an ardent adversary of the Franco regime, responded with profound indignation upon hearing the bombing of Guernica. By chance, he was commissioned to create a mural for the Republican Pavilion at the upcoming World’s Fair in Paris that autumn. The attack on Guernica served as the catalyst for his creative explosion, with a multitude of images already simmering from “Dream and Lie of Franco” ready to erupt onto the canvas.

—

Indeed, shortly following the bombing of Guernica, Picasso completed his initial sketches for what would become the masterpiece known as “Guernica”. The early sketches vividly portrayed scenes of tragedy, including a wounded horse in agony impaled on a spear, a fallen soldier, and a woman witnessing the tragedy from the window of a building.

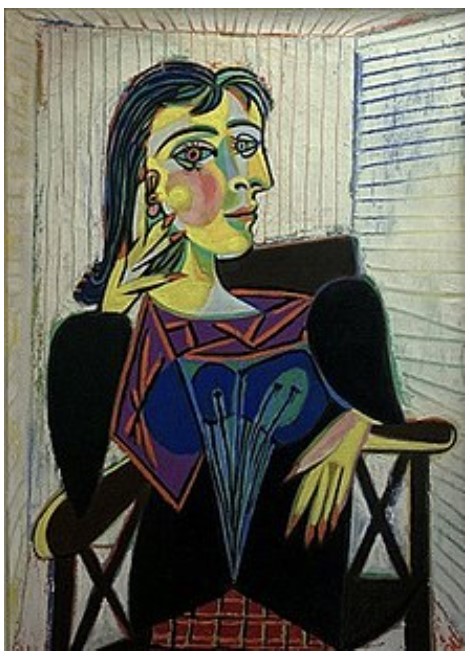

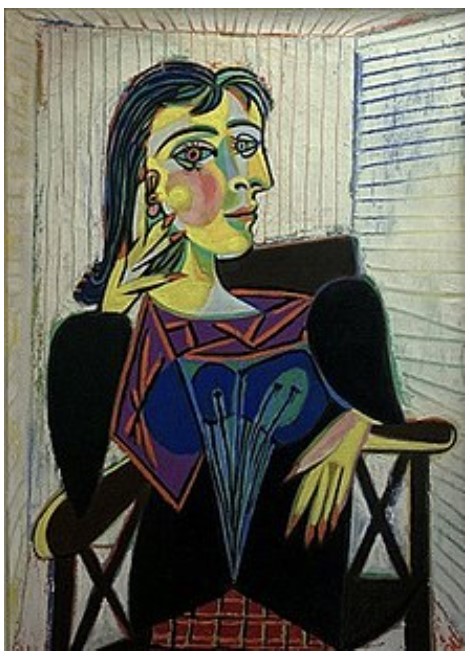

Remarkably, Picasso’s legacy comprises over 60 dated preliminary drawings, sketches, and studies, meticulously chronicling the intricate creative journey that culminated in the final masterpiece. As a result, we have access to much of the day-to-day progress made during the six-month-long creative odyssey of Picasso’s ‘Guernica,’ primarily due to his companion at the time, Dora Maar.

Examining the preliminary drawings of “Guernica” in chronological order reveals a gradual transformation from rudimentary sketches outlining the composition to intricate and elaborate depictions. Throughout this progression, a myriad of motifs come to the fore: the anguished and contorted horse, the juxtaposed presence of a steadfast bull, a mother descending a ladder gracefully while cradling her child, fallen soldiers, and mourning women. Notably, it appears that Picasso made a deliberate artistic decision to abstain from portraying the physical cityscape or directly portraying the affected individuals and streets, despite the magnitude of the tragedy that claimed the lives of approximately 10,000 inhabitants.

—

III. The Interpretations

of Motifs in Guernica

Indeed, to this day, ongoing discussions and debates ensue regarding the significance embedded within each motif in “Guernica.” For instance, the horse at the center emitting a piercing cry of anguish, has been construed as an embodiment of the suffering Spanish populace under Franco’s authoritarian regime. On the other hand, the woman holding a lantern and leaning out of a window on the right side is seen as other European imperialist countries calmly observing the turmoil in Spain. However, at the center of the debate are the interpretations revolving around the motionless and expressionless bull standing quietly at the left edge of the painting.

1. Juan Larrea and Camilo José Cela

Juan Larrea and Camilo José Cela, eminent Spanish critics, contended that the bull represents the enduring Spanish populace, a venerated totemic creature from ancient times. They opined that the bull epitomizes the indomitable essence of the Spanish nation. In contrast, another Spanish critic Vicente Aleixandre posited a different perspective, suggesting that it is the horse that symbolizes the Spanish people, while the bull embodies the fascist violence that subjugates them. It is intriguing to observe these varying interpretation among Spanish critics who share the same national identity as Picasso.

—

2. Wilhelm Boeck

Offering a middle ground, Wilhelm Boeck proposed a compromise by putting forth an argument that the bull and the horse do not stand as separate entities but rather symbolize distinct aspects of the Spanish nation. As Boeck put, the bull represents the continuity of the Spanish state, while the horse represents the innocent lives lost in its history. Together, they symbolize the entirety of the Spanish nation.

3. Carla Gottlieb

According to French critic Carla Gottlieb, the bull takes on a different symbolic role, representing France and its turning away from the horse and the people in the tragedy is attributed to France’s non-interference policy in the Spanish Civil War. Furthermore, Gottlieb explains that the woman kneeling at the bottom right of “Guernica”, bearing a hammer and sickle emblem on her chest, represents the Soviet Union. Unlike France, the Soviet Union actively intervened from the “east” to support the Spanish Republic.

4. William Darr

William Darr suggests interpretations on the basis of a completely different context. According to Darr, the motifs within “Guernica” illustrate a struggle between “death” and “Eros.” In his analysis, Darr divides the painting into two halves. On the left side, he discerns the bull, the mother, the horse, and the soldiers, collectively representing the realm of “Eros.” Darr contends that the bull’s horns symbolize masculinity in a Freudian context, while the window on the right side embodies femininity. He further asserts that the principle of “Eros” invariably intertwines with the principles of “struggle” and “death”, which unfold in Picasso’s unique artistic world. In this light, “Guernica” is undoubtedly one of Picasso’s iconic works.

—

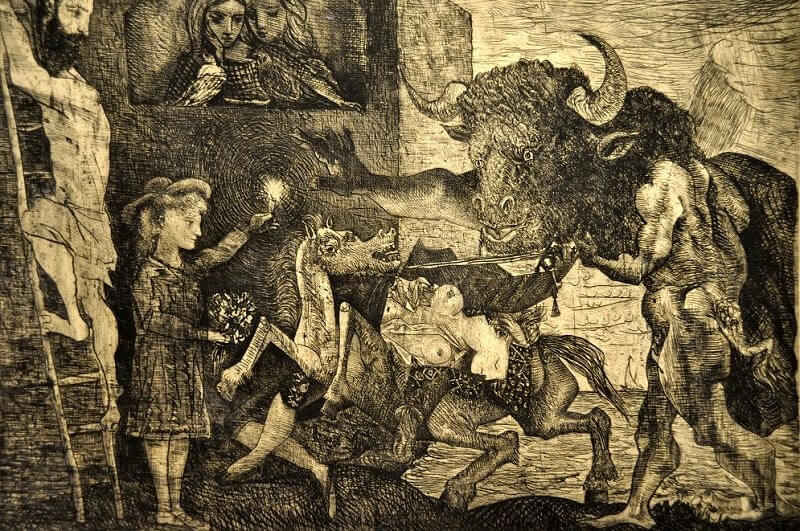

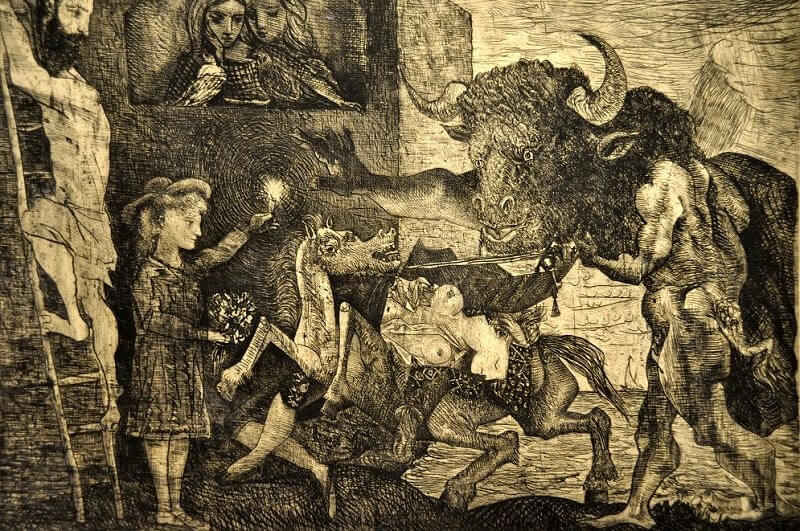

5. Minotauromachy

What then, was Picasso’s thoughts on the bull in “Guernica”? In 1944, when Allied forces entered Paris, a U.S. soldier reportedly inquired of Picasso as regards the meaning of the bull. Picasso, in response, clarified to the soldier that the bull need not be confined solely to representing fascism, rather, it embodied a broader symbol of violence and darkness. Interestingly, in Picasso’s “Minotauromachy” that was created in 1935, predating both “Guernica” and “Dream and Lie of Franco,” he had already depicted the Minotaur, a creature that bears the duality of human and bull, as a monstrous figure symbolizing violence.

Beyond the Minotaur, the artwork encompasses a diverse array of characters. Among them were a girl illuminating the scene with a lamp, a horse, a woman distressed by the Minotaur’s violence, women gazing beyond a menacing spear, and a figure ascending a ladder. Though slight variations, many of the characters later populate “Guernica”. Picasso stuck to recurrent utilization of specific key motifs throughout his lifetime in his artworks.

IV. The Composition of Guernica

1. Pyramid-like Composition

Even a glimpse on “Guernica”, the overall structure of Picasso’s masterpiece can be identified as a composition resembling a pyramid. Slightly left of center resides the lamp, which serves as the apex of this visual formation and its illumination stretches towards the periphery of the canvas. Notwithstanding the apparent simplicity of this arrangement, the artwork emanates a palpable tension and forcefulness owing to Picasso’s skillful orchestration. In fact, the figures within “Guernica” are densely positioned and fill the entire canvas and evoke a profound sense of intricacy despite the apparent simplicity of the pyramid structure.

—

2. Auguste Preault “Tuerie” (Slaughter)

Indeed, the inspiration of the tension-filled arrangement of figures in “Guernica” was drawn from the relief sculpture “Tuerie” by the Romantique artist Auguste Préault. In “Tuerie” in which the slaughter of women and children is depicted in a fierce and eerie way, we find a plethora of figures, among them a woman clutching her elongated neck and a grieving mother cradling a lifeless child. Remarkably, these motifs bear a striking resemblance to those seen in Picasso’s “Guernica.”

Within “Tuerie,” a menacing soldier wearing a helmet serves as the apex of a pyramid structure of the sculpture. It aligns with the section in “Guernica” where the lamp and the head of the bull are located. Moreover, as regards color selection, “Guernica” in which black and gray tones are predominant with minimal use of color also reflects the idea of the relief sculpture. Hence, it becomes evident that Préault’s ‘Tuerie’ not only influenced the theme and composition of Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ but also played a role in shaping its color palette.

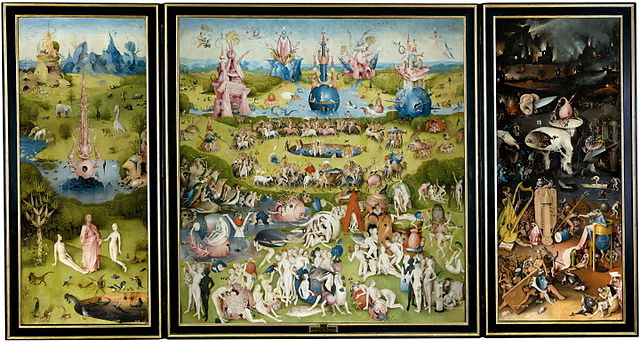

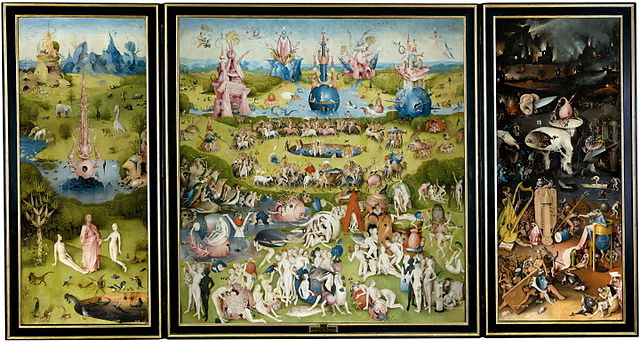

3. Triptych Format

In addition to the aforementioned structural elements, “Guernica” incorporates another compositional aspect reminiscent of late Middle Ages art in various Northern European regions—the triptych format. A triptych consists of three panels or sections, typically hinged together, with a central panel flanked by two smaller panels. Each panel conveys a different scene or image, yet collectively they form a cohesive narrative or thematic unity. In “Guernica”, one can discern a similar structure, featuring distinct sections or compartments within the composition. This triptych-like format juxtaposes diverse elements, amplifying the artwork’s overall visual impact and storytelling prowess.

As pointed out by Professor Arnheim, the canvas of “Guernica” is markedly wider horizontally compared to typical paintings. Notably, none of the preliminary sketches leading to “Guernica” have such an elongated horizontal format as the final painting. In any event, the width of the “Guernica” canvas is slightly more than twice its height, creating an almost 2 : 1 ratio between the horizontal and vertical dimensions.

Upon vertical division into four equal sections, the right end of “Guernica” is filled with the motif of a woman falling from a burning house, while the left side of the painting reveals a mother cradling a child, steeped in mourning. Within the square formed by the amalgamation of these two central sections, we discern the presence of a horse alongside a woman, gently clutching a lamp.

—

Furthermore, these left and right panels exhibit motifs that complement each other in terms of composition. On the left upper part is the tail and horns of the bull and the counterpart is the flames of fire on the right upper part. While the left lower part features the hands and heads of soldiers, it goes along with the legs and knees of a woman at the right lower part. In this regard, there exists no ambiguity that this triptych-style configuration was deliberately orchestrated. Despite the complexity of the figure placement, the canvas retains a sense of order, thanks to this clear triptych format.